Jake's Christmas Mistake

Jake is so sweet it's hard to not want to keep him. I have a penchant for little black dogs.

This is Jake! Jake is three years old, and like many three year old dogs, he occasionally makes errors in his assessment of what is ok to eat. I thought Jake would be an interesting case to share, as (unlike mouse tumors) this is a problem that we encounter very frequently and I wanted to give you some insight as to how we work through these cases and why we make the recommendations we do.

I first saw Jake on December 22. At that point his owner told me that he was active and energetic, but had been vomiting once to twice daily, and that morning he had vomited up his breakfast and the rice she had tried to feed him a couple of hours later. On physical exam, Jake was bright and interested in what I was doing, and did not have fever, dehydration or abdominal pain, all of which are red flags to me that there is potentially something sinister underlying a dog's vomiting.

Jake's owner and I discussed that none of his exam findings were alarming. We discussed starting some diagnostic tests, but Jake's owner said that she would prefer to try some supportive care and to monitor him for a couple of days to see if he improved. Over half of the dogs that I see for vomiting will improve with supportive care, so I agreed this sounded entirely reasonable and Jake's owner said that she would call if there were any dramatic changes.

Jake came back early on the morning of Christmas Eve. His owner told me that he wanted to eat, and kept looking at his food dish longingly, but whenever he ate something he vomited it back up.

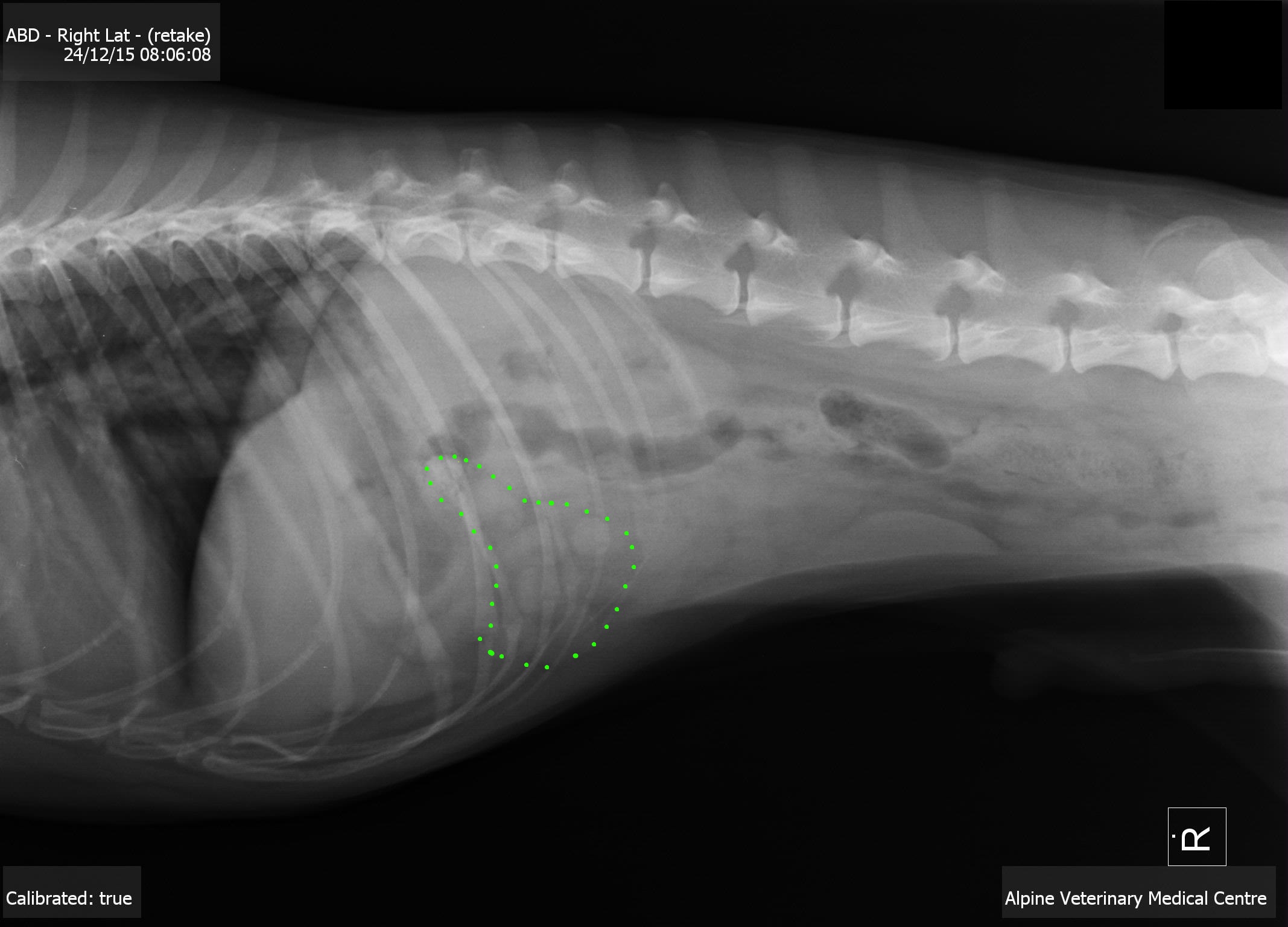

When I see young dogs that are full of energy but can't keep anything down, I start worrying about possible obstructions in the stomach or bowel. Dogs that are more obviously "sick" and showing signs such as diarrhea, dehydration and fever are dogs where I worry about infectious or metabolic disease, like pancreatitis or kidney failure. Jake did not seem like a sick dog, so I recommended taking x-rays to see if we could find an obstruction.

This x-ray is looking at Jake from the side - his head is on the left, and his tail is to the right. The area outlined in green shows bunched, abnormal looking intestines.

Jake's x-rays fell in the frustrating grey area of "not awful and not normal." I was worried that he had some bunching of his intestines behind his stomach, and that his spleen was displaced relative to where it would be normally found. Jake's owner and I discussed that while I was suspicious he had a bowel obstruction, I couldn't prove it. While there was a chance that we could do an exploratory surgery and turn up nothing, there were severe consequences to missing a bowel obstruction, including lack of food and water absorption, death of bowel tissue, and possible sepsis or death.

We agreed to perform an exploratory surgery, and after getting Jake set up with pain medication and iv fluids, we opened his abdomen to see if we could identify the problem. I gave a little cheer when I found an obstruction in the pylorus - this is where the stomach narrows and joins with the small intestine, and is a common location for obstructions. Because the obstruction was in the pylorus and not further along in the small intestine, it meant I could make my incision in the stomach, which heals much more readily than intestine. Obstructions in the intestine often result in the death of intestinal tissue due to the pressure of the obstruction pressing against the intestinal wall, but because this obstruction was in the stomach, all of the intestinal tissue was healthy.

I removed the obstruction from the pylorus - a bit of tugging was involved as the power of the stomach walls contracting had it wedged in quite firmly - and sewed up the incision in the stomach.

Jake's stomach incision closed. The suture material is broken down by the body over the next 9 weeks after the incision has healed.

I then checked the rest of the bowel to ensure there were no other obstructions - this is an important step as it's embarrassing (and negligent) to remove one obstruction and to leave another one behind.

After checking the rest of the bowel, I closed Jake's abdominal incision and monitored him while he woke up. We used this time to try and figure out what it was he had eaten:

I have no idea what this is. It says 'Sony' on it.

Jake woke up quickly and smoothly, and a couple of hours after waking devoured a bowl full of food. I hope Jake makes more responsible decisions about what to swallow in 2016.